N.T. Wright and the Faithfulness of Paul: Part 8: Eschatology and Romans 9-11

I am blogging my way through N.T. Wright’s Paul and the Faithfulness of God, creating an outline of the book as a part of a class I am teaching at our church. This is the eighth of a nine-part series. All quotations followed by a number in parenthesis are quotes from the book. Check out the previous posts here: Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 | Part 6 | Part 7

Part 8: Eschatology and Romans 9-11

Paul and the Faithfulness of God, Chapter 11, Sections 6.4 – 7

I. Approaching Difficult Terrain

“It is easy to be overwhelmed by Romans 9-11: its scale and scope, the mass of secondary literature, the controversial theological and also political topics, and the huge and difficult questions of the overall flow of thought on the one hand and the complex details of exegesis and interpretation on the other.” (1156) We approach Romans 9-11 admitting the difficulty of the challenge before us. Those who say Romans 9-11 is easy to understand and easily applied to our lives haven’t taken the time to seriously read these 90 verses. N.T. Wright discusses this section in the context of eschatology, but these three chapters are connected to monotheism and election, and belong to the rest of the book. They are “bound into the letter’s whole structure by a thousand silken strands.” (1157)

Romans 9 is filled with questions related to God’s future purposes. This chapter is a retelling of Israel’s story from God’s election of them for a specific job to the exodus event with Moses and Pharaoh, including some comments from the prophets. This section (Romans 9-11) follows logically from where Paul leaves off in Romans 8, where he has discussed the life and love experienced by those who are in the Messiah. Romans 9 deals with those who have not believed, primarily those of Israel who have not believed in Jesus the Messiah.

II. Artistic Structure of Romans 9-11

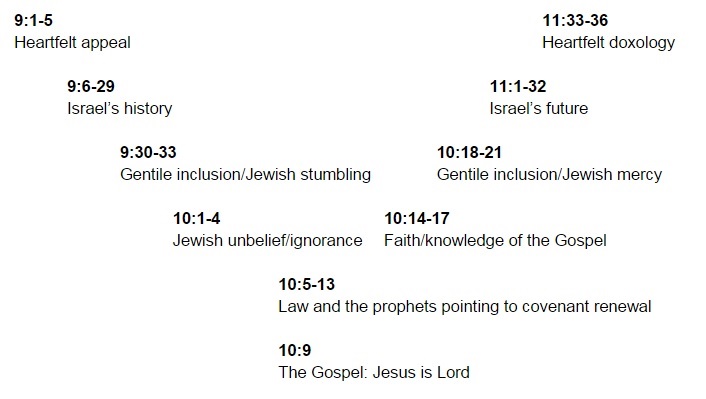

One of the most helpful tools in understanding this section is to see the structure and counter balance of the ideas presented with the central thought found in Romans 10:9.

A. Starting in the middle (Romans 10:1-17)

In quoting from Deuteronomy 30 in Romans 10:6-8, Paul is using language to describe the renewal of the covenant and the end of exile. The “righteousness based on faith” (Romans 10:6) is picture of the “faith-based covenant” (1169). In Deuteronomy 30 it is a commandment which is not in heaven or beyond in the sea, but in the mouth and circumcised heart of God’s people so they can obey. In Romans 10, Paul says the word is in your mouth and heart. This word (or message) is the Gospel: “ if you confess with your mouth that Jesus is Lord and believe in your heart that God raised him from the dead, you will be saved.” (Romans 10:9) Paul is still talking about justification, that is the one God’s declaration (redefined monotheism) of those who are in the right as members of the one covenant people (redefined election), a future act God is declaring in the present (redefined eschatology). The Jewish people were seeking to establish their own covenant membership (Romans 10:3), but justification and salvation were not only for those with Jewish ethnicity, but for both Jew and Greek alike (Romans 10:12-13). Jesus the Messiah is the end, the termination point, of the torah making covenant membership available to those who wear the badge of faith (Romans 10:4). The God of Israel intended on circumcising the hearts of his people (Deuteronomy 30:6) so there would be a “new way of doing the law” (1173). According to Paul, preaching becomes necessary in this new way. Preaching the Gospel is the announcement that the one God of Jews and Gentiles has become Messiah and King in and through Jesus. Salvation, in addition to justification, is now available for Jews and Gentiles. Keeping Paul’s conclusions in these verses in mind can prevent us from getting lost in Paul’s longer arguments regarding Israel in Romans 9 and 11.

B. Taking a step back (Romans 9:30-33 and 10:18-21)

Paul sums up in four verses the case he has been building in Romans 9, God choose Israel to be examples of his righteousness, but they have stumbled because they pursued righteousness, that is a covenant status, not by faith, but by the torah. This line of thinking takes us further back to Romans 7 and 8. The torah gives sin an opportunity to spread, but God condemns sin in the flesh of Jesus the Messiah (Romans 8:3). Romans 9 describes the election of Israel and their stumbling, but there is no mention of sin, although Roman 1-8 deals often with the topic if sin. In pursuing a covenant status formed by the torah, Israel ends up stumbling over the very intent of the law and ultimately the goal of the torah, Jesus the Messiah. The Jewish stumbling in Romans 9:30-33 intended to make the Gentiles jealous as described in Romans 10:18-21. Paul draws upon Moses (Romans 10:19) and Isaiah (Romans 10:20) as witnesses to the fact that “Gentiles were going to be brought in to make Israel jealous.” (1180) The hope for Israel is while God has included Gentiles in the covenant family, those who have pursued covenant membership by faith, God still holds out his hands of mercy towards Israel (Romans 10:21).

C. Israel’s Strange Purpose (Romans 9:6-29)

This section is, in part, a retelling of the story of Israel beginning with Abraham. “This, in fact, is how (second-temple Jewish) eschatology works: first you tell the story of Israel so far, and then you look on to what is still to come.” (1181) Paul is talking about eschatology, but Jewish eschatology includes a recounting of God’s activity in history. In one sense, we could read Romans 9 as speaking of the past, Romans 10 dealing with the present, and Romans 11 as Paul’s discussion of the future. Paul is recounting Israel’s story in light of where that story goes namely to the coming of Jesus the Messiah who does for Israel what Israel could not do for herself. The God of Israel has been active in history “showing mercy” and “hardening” in order to fulfill his purposes. Paul is not retelling Israel’s history to demonstrate how God saves people in general using Israel as an example. Rather Paul is describing God’s action in and surrounding Israel, because it is in and through Israel in particular that God has chosen to save the world.

This retelling of Israel’s election is told from a Jewish point of view to point out to Gentile believers in Jesus the Messiah that they have been included in a irreplaceable story of God’s purposes in and through Israel. Paul’s emphasis is God has shown mercy to Jacob (i.e Israel) a part from Israel’s lack of commitment to the torah. If God can by his grace choose a people unfaithful to the torah then what if God has chosen to be patient with Gentiles these seemingly “vessels of wrath” (Romans 9:22)? Paul uses the metaphor of a potter and clay to describe his dealings specifically with Israel and not all humanity. Israel cannot tell God: “You are unfair in molding us in a certain way!” God has chosen Israel and he is the master potter and can mold pottery in any way he chooses. This act of choosing is what we mean by election. “It is not, then, that ‘election’ simply involves a selection of some and a leaving of others, a ‘loving’ of some and a ‘hating’ of others. It is that the ‘elect’ themselves are elect in order to be the place where and the means by which God’s redemptive purposes are worked out.” (1191)

God’s act of hardening, like his act of electing, was to demonstrate his saving purposes. Paul writes: “What if God, desiring to show his wrath and to make known his power, has endured with much patience vessels of wrath prepared for destruction, in order to make known the riches of his glory for vessels of mercy, which he has prepared beforehand for glory— even us whom he has called, not from the Jews only but also from the Gentiles?” (Romans 9:22-24). By writing “what if” Paul is introducing a new interpretation to Israel’s story. What if God wanted to demonstrate his judgment (wrath) and power (authority) by showing patience towards “vessels of wrath” and revealing the richness of his mercy in his “vessels of mercy” which includes Gentiles? The answer is: this is exactly what has happened in Messiah. Paul quotes from the prophet Hosea to answer the question: “Those who were not my people I will call ‘my people,’ and her who was not beloved I will call ‘beloved’” (Romans 9:25, quoted from Hosea 2:23).

D. Israel’s Mysterious Future (Romans 11:1-32)

Paul asks another rhetorical question: “Has God rejected his people?” He answers: “By no means!” (Romans 11:1) If Romans 9 is a retelling of Israel’s history (election) then the counter-balance is an account of Israel’s future in Roman 11 (eschatology). Israel has been seemingly “cast away” for a purpose, that would ultimately lead to their acceptance. The inclusion of Gentiles was not a sign indicating the God of Israel has rejected his people, rather it was to make Israel jealous. Israel is also invited to participate in the reconciliation of Jesus the Messiah. Paul writes, “For if their rejection [casting away] means the reconciliation of the world, what will their acceptance mean but life from the dead?” (Romans 11:15) The covenant is renewed for the Jewish people who confess Jesus is Lord which makes them alive. They are experiencing a “partial hardening” (Romans 11:25), not because God has rejected them and replaced them with Gentiles, but that they would become jealous by the Gentile inclusion and “all Israel will be saved.” Israel stumbled (Romans 11:11), was broken off (Romans 11:19), was hardened (Romans 11:25), and “they too have now been disobedient in order that by the mercy shown to you (Gentiles) they also may now receive mercy” (Romans 11:31).

Will all Israel be saved? Paul’s answer is, at first glance, complex. In Romans 11:14 Paul expects “some” to be saved, but in Romans 11:26 he says all Israel will be saved. He is clear: “God has consigned all to disobedience, that he may have mercy on all.” (Romans 11:32) God’s mercy extends to all, Jew and Gentile alike, but will all Israel be saved or just some? The answer is found in looking back at the rhetorical center of Romans 9-11, which is Romans 10:9-13: “..If you confess with your mouth that Jesus is Lord and believe in your heart that God raised him from the dead, you will be saved. For with the heart one believes and is justified, and with the mouth one confesses and is saved. For the Scripture says, ‘Everyone who believes in him will not be put to shame.’ For there is no distinction between Jew and Greek; for the same Lord is Lord of all, bestowing his riches on all who call on him. For “everyone who calls on the name of the Lord will be saved.” In this regard, Jews cannot boast and neither can Gentiles. Gentiles have been grafted in and if Jews have been broken off, God has the power to graft them in again. Salvation for Israel is the same as salvation for the Gentile nations; it is found in a covenant status pursued by faith in Jesus the Messiah.

E. The Beginning and the End (Romans 9:1-5 and Romans 11:33-36)

This section follows the pattern of many of the Psalms, by opening with a lament and closing with praise. Pauls opens with: “I have great sorrow and unceasing anguish in my heart. For I could wish that I myself were accursed and cut off from Christ for the sake of my brothers, my kinsmen according to the flesh.” (Romans 9:2-3) He closes this section with: “For from him and through him and to him are all things. To him be glory forever. Amen.” (Romans 11:36). “Paul is doing again what he does best: expounding the ancient faith of Israel, rethought and reimagined around Jesus and the spirit, in such a way as to take every thought captive to obey the Messiah.” (1256)

III. Summing Up Paul’s Theology

Paul has taken three Jewish paradigms—monotheism, election, and eschatology—and thoroughly reworked them in light of Jesus the Messiah and the coming of the Spirit. In doing so he has transformed the hope of Israel by bringing the Jewish law to its intended termination point. The covenant has been renewed as promised. Yahweh has been faithful to the covenant and has returned to his people who are marked by faith in the Messiah. His Spirit now dwells in his rebuilt temple, that temple made with stones that breathe. His final act of judgment has been experienced by those in the body of Messiah. Both Jews and Gentiles have been declared in the right and thus members of God’s covenant family. Gods action of blessing, saving, and healing God’s world has begun, but it is not complete. God has been faithful to his promise to Abraham, a faithfulness to the covenant that has been displayed by the faithfulness of Jesus the Messiah.

IV. Final Thoughts

The Gospel is for the Jew first and also for the Greek, the Gentile, the non-Jew. The Gospel declares how the God worshiped by the Jews has become the King of the world. The future for Israel and Gentile nations depends on how they respond to the Gospel.