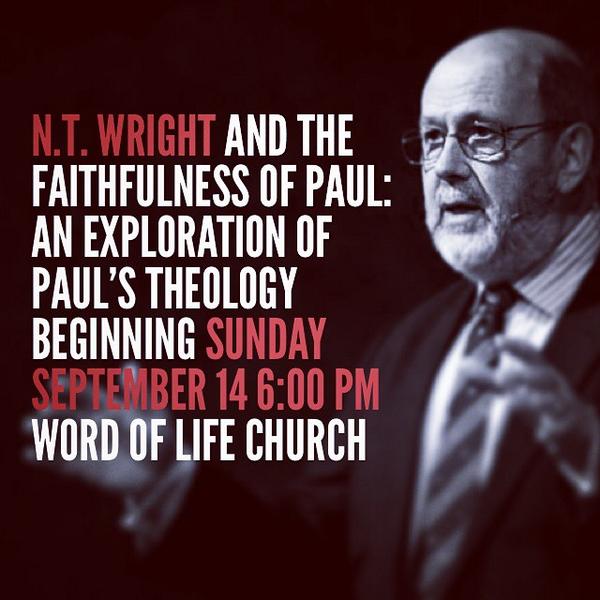

N.T. Wright and the Faithfulness of Paul: Part 2: Birds in Paul’s Head

I am blogging my way through N.T. Wright’s Paul and the Faithfulness of God creating an outline of the book as a part of a class I am teaching at our church. This is the second of a nine-part series. All quotations followed by a number in parenthesis are quotes from the book.

N.T. Wright and the Faithfulness of Paul

Part 2: Birds in Paul’s Head

Paul and the Faithfulness of God, Chapters 2-5

I. Paul’s Historical Context

“Paul lived and worked, in fact, in at least three worlds at once, each of which is subdivided. His life and work must sometimes have appeared just as bewildering to those who lived in those worlds as it does to us in our attempts to reconstruct them (and to understand him). In fact, much more so. We have two dangerous advantages: length of hindsight, shortage of material.” (75)

A. These worlds are Jewish, Greek, and Roman

They were each distinct, but deeply intertwined worlds alive in Paul’s imagination & thoughts.

B. A review of worldview within a cultural setting

1. Praxis: What were the common practices?

2. Symbol: What were the key symbols?

3. Story: What narratives shaped the culture?

4. Question: What were the BIG questions people were asking?

II. Hovering Birds: The Jewish World

“What I am…concerned with here is certain emphases and angles of vision, rather than a major retelling of the story of the Jews in the first century or a major new sketch of their worldview, beliefs and hopes. I hope in particular to bring out the way in which the faithfulness of Israel’s God functions as a theme throughout so much of the period.” (77)

A. The Pharisees

Pharisees were a popular and influential movement of Jews in the first century concerned with religious and civic/social purity, not in terms of personal holiness, but as a “sign and seal” of loyalty to Israel and to Israel’s God.

The heart of Pharisaical life was prayer, rooted in the Shema (Hear O Israel the LORD is our God, the LORD is one), but Pharisees were a kingdom-of-God, and thus political, movement. They shared with the Zealots a “zeal,” for the Kingdom of God, meaning they were prepared to enter in a holy war as instruments of the reign of Israel’s God.

“Zealous” did not mean wholeheartedly devoted or passionate, but willing to become violent. N.T. Wright points to the use of the “zealous” in the Maccabean revolt.

Paul, after being arrested in Jerusalem, writes: “I am a Jew, born in Tarsus in Cilicia, but brought up in this city, educated at the feet of Gamaliel according to the strict manner of the law of our fathers, being zealous for God as all of you are this day.” (Acts 22:3)

B. The Torah

The Jewish law (Torah) was a matter of both praxis and symbol. It contained “precise patterns of behaviour” (91) and it served as a powerful symbol in Jewish imagination. The Torah was designed to form Israel into a distinct people separate from the pagan Gentile nations. For example, it contains strict laws regarding who you share your table with or what kind of food you eat.

C. The Temple

“The Temple in Jerusalem was the focus of the whole Jewish way of life. A good deal of Torah was about what to do in the Temple, and the practice of Torah in the Diaspora itself could be thought of in terms of gaining, at a distance, the blessings you would gain if you were actually there – the blessing, in other words, of the sacred presence itself, the Shekinah, the glory which supposedly dwelt in the Temple but would also dwell ‘where two or three study Torah’.” (95)

The Temple is where heaven and earth met. The backbone of Israel’s prayer life was the picture of Yahweh (the LORD) dwelling in the temple. For example: “O God, you are my God; earnestly I seek you; my soul thirsts for you; my flesh faints for you, as in a dry and weary land where there is no water. So I have looked upon you in the sanctuary, beholding your power and glory.” (Psalm 63:1-2)

“The Temple was a microcosm of the whole creation.” (101) It points to new creation, where God will dwell with his people forever (Revelation 21:3).

The symbols of “temple, presence, glory, kingship, wisdom, creation, exile, rebuilding, and unfulfilled promise —would be part of (first century Jewish) mental and emotional furniture.” (107)

D. Jewish questions asked in the first century

The Jewish people felt like they were “living in a story in search of an ending” (109). So they were asking: We are still in exile. When will Yahweh return to the temple? How could this God not act at last to fulfil his promises?

Groups like the Pharisees, were not looking to the Torah or the Temple asking, “How do we earn God’s favor so in the afterlife we can avert God’s anger?” They were asking, “When will Yahweh come rescue us, renew the covenant, and thus rescue the entire world?”

E. The Continuous Story of Israel

“The (Hebrew) Bible was not merely a source of types, shadows, allusions, echoes, symbols, examples, role-models and other no doubt important things. It was all those, but it was much, much more. It presented itself as a single, sprawling, complex but essentially coherent narrative, a narrative still in search of an ending.” (116)

The story of Israel, or at least large portions of the story of Israel, are told and retold throughout the Old Testament. This tradition is carried on by Paul and other New Testament figures (e.g. Peter’s sermon at Pentecost, Stephen’s sermon before his stoning, Paul in Romans and Galatians). The prophets begin to look forward to the coming of Messiah.

There is no one single picture of what Messiah looks like, but in many of the retellings of the story of Israel there is a longing and waiting for Messiah.

F. The second-Temple period was a continuation of the exile

The Jews of Paul’s day (a period of time N.T. Wright calls “second temple judaism”) were back in their homeland after the Babylonian/Persian exile but living under the boot of the Roman Empire symbolized the continuation of the exile.

Many determined from studying the Torah that they were still in exile, because they had not been faithful to the covenant. Therefore groups like the Pharisees were encouraging strict adherence to the Torah so as to be saved. The second-temple Jewish understand of salvation was not “other-worldly” (i.e. going to heaven after death). Their view of salvation was earth-bound. They wanted to be saved from Roman oppression, saved from sin (idolatry and injustice) in order to be the agency for God to do his work of saving the world. “The rescue of human beings from sin and death, which remains vital throughout, serves a much larger purpose, namely that of God’s restorative justice for the whole creation” (165).

The coming of the day of salvation was seen as the coming of a new age, a new epoch of human history. The salvation life they expected to live was the life of this coming age, that is the life of the age to come, or “eternal life” for short.

G. The theology of a Pharisee: Three categories: monotheism, election and eschatology

1. Monotheism: the worship of Yahweh, the one true living God who is the creator of all, yet distinct from his creation, and the God who revealed himself to Abraham, Moses, et. al. Pharisees believed in a “creational and covenantal monotheism” (180).

2. Election: Israel was chosen by God to live in covenant with him as a part of his plan to rescue and redeem the whole world.

3. Eschatology: God’s future for God’s world, God making the world right

To sum up these three in the context of Paul’s Jewish world, we could say: Yahweh, the God of Israel had chosen Israel to be the people through whom God would use to fill the whole world with his glory. (Psalm 72:18, Num 14:20-23, Hab 2:13, Is 11:9)

III. Athene and Her Owl: The Greek World

“Paul did not derive the central themes and categories of his proclamation from the themes and categories of pagan thought, that doesn’t mean that he refused to make any use of such things. Indeed, he revels in fact that he can pick up all kinds of things from his surrounding culture and make them serve his purposes….All wisdom of the world belongs to Jesus the Messiah in the first place, so any flickers or glimmers of light, anywhere in the world, are to be used and indeed celebrated within the exposition of the gospel.” (201)

A. The symbol of the owl

The owl in Greek (hellenistic) culture came to represent “seeing.” The Greek philosophical tradition was built upon seeing what others could not see.

B. Religion or philosophy?

From a Greek point of view, Paul was doing three things which would be perceived more as philosophy than religion. (1) Paul presented a different order of reality beginning with a creator God who had broken into creation. (2) Paul taught and modelled a particular way of life quite different than the way of life known by the Greeks. (3) Paul established and maintained communities resembling the many philosophical schools of the ancient world.

C. Popular Greek schools of philosophy

1. The Academy (Plato; Platonism): The world of space, time, and matter was an illusion and less real than the world of “forms” or “ideas,” which is ultimate reality. (e.g. The Allegory of the Cave)

2. The Lyceum (Aristotle; Aristotelian thought): The material world should be analyzed and categorized in the pursuit of virtue and human flourishing (Greek word: eudaimonia).

3. The Stoics: All material things are indwelt with divinity (Greek word: pnuema) (pantheism). The goal is to become a sage, wise, self-sufficient, and in harmony with the way things are.

4. The Epicureans: The gods are far removed (dualism); we have no eternal soul, so pursue tranquility and happiness in this life. (Note: This was not hedonism.)

“Whereas the default mode of most modern westerners is some kind of Epicureanism, the default mode for many of Paul’s hearers was some kind of Stoicism.” (213)

D. Greek praxis

Philosophy, even for Platonists, was not detached from everyday life. Philosophy was a way of life. The goal was to be able to see in the dark.

E. Greek symbols

Stoics, as one example of Greek culture, wore simple clothes, ate plain food, lived without much luxury.

F. Greek stories (myths)

Platonists told creation stories. The Allegory of the Cave became a founding myth. Stoics told stories of creation by the logos or pneuma working with the primary elements: fire, air, earth and water. Many Greek stories focused on the hero, becoming the invention of the modern individual (e.g. Hercules, Achilles, Odysseus, Perseus).

G. Greek questions

What is there? (physics) ⁃ What ought we to do? (ethics) ⁃ How do we know? (logic)

IV. A Rooster For Asclepius: Pagan Religion

There was a overlap between philosophy and religion in the pagan, Gentile world of Paul. The Philosophers often spoke of the gods. There were a number of religions being practiced in the ancient world of Paul. His pattern of religion was different than those around him. His proclamation of a crucified Messiah was “a stumbling block to the Jews and foolishness to the Greeks” (1 Corinthians 1:23).

Religion was not separated from public life. Religion was the very fabric of society. Pagan religions had temples, sacrifices, festivals, and the like. Religion was a matter of action more than belief. Paul’s preaching challenged people to a new and different life.

V. The Eagle has Landed: The Roman Empire

Rome took the eagle as its symbol for its power, beauty, and prestige. Rome in the day of Paul was ruled by the Caesar who installed local governors to oversee law and order throughout the empire. Augustus, the first Roman Emperor, was called “Son of the Deified” (Latin: divi filius). Caesar ruled the land promised to Messiah.

“Rome brought ‘peace’ to the world, at the usual price: submit or die.” (284) “After sixty years (of Roman civil war), they were ready for (peace). Ready, too, to make it divine, and to associate it with the man who had brought it: pax Augusta. It was this ‘peace’ that allowed the apostle Paul, under Augustus’s successors, to travel the world announcing a different peace, and a different master.” (288-289)

A. List of first century Roman Emperors

27 BC-14 AD Augustus (Adopted son of Julius Caesar)

14-37 AD Tiberius (Ruled during the life of Christ)

37-41 AD Caligula

41-54 AD Claudius (Ruled during the early ministry of Paul)

54-68 AD Nero (Ruled during the later ministry of Paul)

69 AD Galba (Ruled for 7 months)

69 AD Otho (Ruled for 3 months)

69 AD Vitellius (Ruled for 8 months)

69-79 AD Vespasian (Ruled during the fall of Jerusalem)

79-81 AD Titus (Son of Vespasian; was the general in the siege of Jerusalem)

81-96 AD Domitian (Arguably the beast from the bottomless pit in Revelation)

B. Roman symbols

The fall of the republic led to the Pax Romana under the Caesar, the Roman emperor, so every cultural tool from literature, to coinage, to art and architecture was used to promote the power and presence of Caesar. For example, a bust of the emperor could be found everywhere in the empire.

C. Emperor worship

The growing popularity of Caesar led to the development of imperial cults, the worship of the Emperor as divinized. There was no one single unified cult, but many different imperial cults throughout the Roman Empire. The imperial cult was not a religion in the modern sense, but an interwoven part of life in the empire where religion, culture, and politics were interconnected.

The Roman Senate voted to divinize Augustus, giving him the title divi filius, meaning “son of God” or “son of the deified one.” Augustus did not want public worship. His was more of an honorific title. The announcement of his rise to power was called the “good news” (Latin: euangelia) that brought salvation to Rome. The worship of the emperor started small and began to grow.

Tiberius was called “son of god,” son of the divine Augustus. Titus demanded to be called “lord and god” (Latin: dominus et deus). By the rule of Titus, “Worshipping the emperors was well on the way to becoming a central and vital aspect not only of life in general but of civic and municipal identity. Whatever we say about either the intentions or the effects of Roman rulers from Julius Caesar to Vespasian, the richly diverse phenomena we loosely call ‘imperial cult’ were a vital part of a complex system of power, communication and control, in other words, of all the things empires find they need to do.” (341)

D. Jews in the Empire

Jews had an eschatological objection to the Roman Empire. (Eschatology=”God’s future”)

“Rome’s claim to have brought the world into a new age of justice and peace, flew, on eagle’s wings, in the face of the ancient Jewish belief that these things would finally be brought to birth through the establishment of a new kingdom, the one spoken of in the Psalms, in Isaiah, in Daniel. Thus, though their resistance to empire drew on the ancient critique of idolatry, the sense that Israel’s god would overthrow the pagan rule and establish his own proper kingdom in its place led the Jewish people to articulate their resistance in terms of eschatology. ” (343)

VI. Final Thoughts

Paul remained a Jewish thinker who communicated to Christian congregations spread out in a pagan world. He may choose imagery from either the Roman or Greek world in his writing, but he does so from the position of a Jewish thinker.