N.T. Wright and the Revolutionary Cross: Week 4

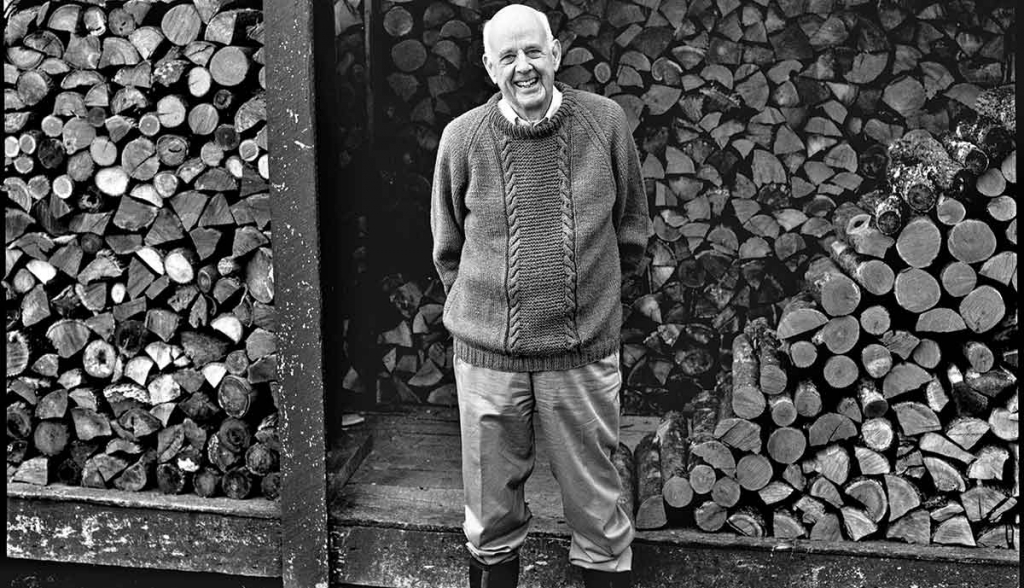

I am blogging my way through N.T. Wright’s book The Day the Revolution Began, creating an outline of the book as a small group study I am leading at our church. This is the fourth of six blogs in this series. All quotations followed by a number in parenthesis are quotes from the book. Click here for previous weeks [Week 1] [Week 2] [Week 3]

The Kingdom of God and the Triumph over the Powers

The Day the Revolution Began (Chapters 10-11)

Chapter 10: The Story of Rescue

When Jesus talks about the kingdom of heaven, as recorded in Matthew’s gospel, he is not talking about a place called “heaven,” where we go upon death, but the “rule of heaven,” that is the kingdom of God. The warnings Jesus gives associated with hell are often directed toward pending disaster in this world, namely the imminent destruction of Jerusalem in 70 AD., even if some references to hell, (Greek word Gehennah), seem to point to something beyond calamity in this world. (For example see Matthew 10:28 and Luke 12:4-5.) If the gospel writers could talk to modern preachers of the gospel, they would most certainly confirm they were proclaiming the gospel, while our speculative theories and propensity to hand-pick individual verses of Scripture have turned atonement into a mechanism rather than the crucial moment when God’s revolutionary kingdom was launched.

While the gospel writers have tended to be ignored when we have turned to the Scripture to understand the meaning of the cross, the time has come to turn up the volume on Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John in order to hear the stories they are telling about the kingdom, the Temple, Pilate, and the mocking crowd. By doing that we can hear the big story they are telling. Listening to these stories guides our journey towards understanding what exactly happened the day Jesus died. During this quest we will find both historical answers and theological answers.

Historically, Jesus died because the chief priests saw Jesus’ ministry as blasphemous. The Romans saw Jesus as a rival king. The Pharisees held Jesus in contempt for challenging their rules. The followers of Jesus abandoned him, including one who betrayed him. Our search for theological answers, asking what was the divine reason Jesus died, cannot continue without taking into consideration the historical answers. For Wright, “The historical questions and answers are the place to go if we want to find the theological answer” (199). Our purpose in paying attention to the historical questions in the gospels is to determine Jesus’ own understanding of his mission and purpose.

When we listen to the gospel writers we can hear them telling the story of Jesus as the long-awaited return of Israel’s God. In fact, they intentionally connect the Jesus story with the story of Israel. Jesus came as the Son of God, the living embodiment of Israel’s God, and Emmanuel, God with us. The life and ministry of Jesus was filled with compassion and love in the gospels. Jesus’ death is the tragic end of the one who embodied the covenant-keeping love of Israel’s God. The gospel writers, particularly John, described the growing hostility towards Jesus (see John 5:18, 7:1, 7:19-20, 7:25, 8:37-40).

Within the story the gospel writers are telling is not only the story of Israel but the story of darkness and evil that has plagued God’s good world. Evil has been depicted throughout the story of Israel in various forms of idolatry and injustice not only by pagan people but by members of the people of God. The patriarchs and the kings, the heros in the up-and-down story of Israel were all flawed, hindered by the ever-presence of evil and sin. Evil is not merely a pagan problem but a disease affecting all people and all creation.

The storm clouds were forming around Jesus from his birth, as Herod sought to kill him before his ministry even got started. The poor responded to his ministry, but his kingdom message did not draw applause from the ruling Jewish elite. The Pharisees opposed him. The chief priests sought to kill him. Rome saw him as a political threat. He taught the way of peace, reconciliation, and self-sacrifice, eclipsing all the traditional Jewish cultural markers. All of this animosity and opposition was how evil coalesced into a single force putting Jesus to death. Jesus had been battling not people and their evil ideas as much as Jesus was battling evil itself. As Jesus drew near to his death he told his disciples, “Now is the judgment of this world; now will the ruler of this world be cast out. And I, when I am lifted up from the earth, will draw all people to myself” (John 12:31-32). Jesus’ death would be a victory over evil by casting out the ruling force behind the evil in the world. This victory was not placed artificially over the story of Israel but reaches its climax with the story itself.

In this way, we can read the gospels as the coming of God’s kingdom being the culmination of Israel’s story, but equally as a story of how evil came together against Jesus wherein Jesus defeats death, evil, and sin itself. In Acts 4, as the followers of Jesus were praying, they quote from Psalm 2 acknowledging that “the rulers were gathered together, against the Lord and against his Anointed” (Acts 4:26). Evil had gathered together in Herod and Pilate at the trial of Jesus, just as Psalm 2 said. When Jesus was arrested he told the chief priests and the temple guards, “this is your hour, and the (the hour of the) power of darkness” (Luke 22:53). The battle Jesus was in was not against flesh and blood but against the power of darkness itself.

The power of darkness is the satan, the “ruler of this world,” who will be cast out by Jesus’ death. The satan entered Judas turning him into “the accuser,” the literal meaning of the word “satan.” This battle with evil is not the convenient backdrop to the death of Jesus which is about something altogether different. Particularly for John’s gospel, the meaning of the death of Jesus is connected to the story he tells, a story of struggle and death, victory and love, a story of Jesus’ death as the defeat of evil according to God’s covenant love. As we have seen, the gospel writers convey to us the words of Jesus about his death at the Passover. Jesus is the Passover lamb who, in the words of John the Baptist, “takes away the sin of the world” (John 1:29). As sin is taken away, a great victory over the power of evil has been won. The coming Messiah rules in the proclamation of God’s kingdom by putting an end to sin. The great themes of God’s kingdom rule and the redemption of the world through the cross are inextricably tied together in the gospels.

Forgiveness of sins, and thus the end of exile, comes about because Jesus bears the punishment of Israel. Jesus brings an end to exile also by redefining the shape of the kingdom of God by his very death. The kingdom of God in contrast to first century Jewish expectations looks like self-giving love and self-denial. As Israel’s representative, Jesus does what Israel was called to do but ultimately could not do, namely, representing the light of God’s truth to the Gentile world. Jesus said, “As Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness, so must the Son of man be lifted up,” a reference to his death (John 3:14). As Jesus was lifted up on the cross, sin and death that had plagued not only Israel, but all mankind, were brought together. When we see the cross and gaze upon the suffering of Jesus we realize our sins have been dealt with. According to Jesus, his death was not to appease an angry God, but rather it demonstrates the love of God, “For God so loved the world, that he gave his only Son…” (John 3:16).

Jesus dies as a rebel in the place of rebellious Israel, as depicted in the crowd’s desire for Barabbas to be released and Jesus to be crucified. The gospel writers make it clear that Jesus was innocent. He had done nothing wrong, yet he was sentenced to death. Even as he hung on the cross, the penitent thief being crucified with Jesus announced that Jesus hadn’t done anything wrong (Luke 23:41). Jesus promised “paradise” to this thief – not heaven, but a restful holdover until resurrection. Within Luke’s gospel we see the powers of darkness are defeated because Jesus dies on behalf of the guilty. Throughout his ministry, Jesus had warned people of coming disaster – not going to hell after death, but real world disaster. Hell in the afterlife is a reality not to be overlooked, but not the primary form of punishment Jesus was talking about.

Jesus dies as a substitute in that Jesus represents Israel as their Messiah. Jesus bears the weight of Israel’s sins and the sins of the world, and dies as the forces of evil collude against him so at long last the kingdom of God may come. The death of Jesus is what it looks like when Israel’s God becomes king of the nations, but it does not look like conventional power. This surprising death of King Jesus revealing the power of the kingdom of God is the power of co-suffering, self-giving love. The kingdom is therefore launched not by the elites of society but by the poor, the meek, the mourning, and the peacemakers. The kingdom will not come through the military might of empire, but through the way of nonviolence, enemy-love, and prayers or persecutors.

By his death, Jesus sets forth a new ethic – the ethic of love and reconciliation that will become the ethic by which God redeems the world. The death of Jesus therefore does not save us from the world by taking us to heaven. Rather the death of Jesus saves us for the world, a powerful revolution within the world, a vision found among Israel’s prophets. Israel was always called to be the means by which the kingdom of God would come, but the means by which the revolution began took most of Israel by surprise. The Messiah came into this world born of a virgin in Bethlehem, but he came with the words of peace and forgiveness on his lips. The very nature of power had to be radically reimagined by the followers of King Jesus. According to Wright, “A new sort of power will be let loose upon the world, and it will be the power of self-giving love. This is the heart of the revolution that was launched on Good Friday” (222). The powers are overthrown by the death of Jesus in part because Jesus was powerless in his death.

As we step back and take a bird’s-eye view of what we see about the death of Jesus in the gospel, we find the following predominant landmarks. First, the gospel writers do not give us bits of information that we need to factor into a formula or theory about what the death of Jesus really means. Rather the meaning of Jesus’ death is found in what they have written. According to Wright, the “formula” is in fact a “portable narrative, a folded-up story” (223). We resist any attempt to understand the death of Jesus apart from the historical context, which has much to say about the kingdom of God coming to Earth.

Second, before we begin to look at how Paul deals with the cross in his letters, we acknowledge the revolutionary and kingdom-nature of the cross. In this wide-angle view of the cross, we do not lose the truth that Jesus died for our sins, which has personal implications for all those who believe. Individual faith and responsibility are still intact, but we as modern individuals are invited into a larger story that is more than going to heaven when we die. We find ourselves in a story of creation, covenant, and new creation, a story we repeat as we come to the communion table, a story we live out as we cooperate with the Spirit’s work of peace and reconciliation.

Chapter 11: Paul and the Cross (Apart from Romans)

The Apostle Paul had much to say about the death of Jesus. Traditional atonement theologies have had the tendency to look first to Paul, running right past the gospels and much of the Old Testament. But just as we want to ground our understanding of the death of Jesus in its historical context, we also want to ground our reading of Paul in his historical context. Paul used a variety of different images to describe the cross of Christ. We can develop a singular vision of atonement based on one of these images, which some have done with the penal substitution theory from the perspective of the works contract. We do find both “penal” and “substitutionary” aspects to the death of Jesus, but these are not the only images Paul uses. Reducing the atonement to only the penal substitutionary view limits our understanding of the cross, because Paul has more to say about the death of Jesus.

Two overarching concepts to keep in mind as we look at what Paul has to say about the cross are (1) the story of redemption is moving towards new creation and (2) the death of Jesus is the means by which new creation is attained. Jesus takes upon himself the divine condemnation of sin on behalf of Israel and the world. This sacrificial act becomes the supreme revelation of God’s love, the very covenant-faithful love we see throughout the story of Israel. Paul proclaims the power of the cross (1 Corinthians 1:18). However he does not explain precisely why or how the cross has the power it has. So while we do not know how the cross is powerful, Paul does identify the effects of the cross which includes both the salvation of those who believe and the driving out of “rulers of this age” (1 Corinthians 2:6).

As we have discovered, Paul delivered to the churches as it was received that “Christ died for our sins in accordance with the Scriptures” (1 Corinthians 15:3). In other words, Jesus the Messiah died for our sins according to the story of Israel. The expectation of Jewish believers in Jesus was that the death (and ultimate resurrection) of Jesus would establish the kingdom of God (see Luke 23:42, Acts 1:6). The various images Paul used are not random metaphors but all find their cohesion and definition in the Old Testament. Behind all Paul revealed about the death of Jesus stands the truth that Jesus died as Israel’s Messiah. The English word “Christ” comes from the Greek word christos which means “anointed one.” The Jewish tradition was not to coronate their kings. Rather, they anointed them with oil. The Hebrew word for “anointed one” is mashiach, best translated in English as “Messiah.” Christ or Messiah was the Jewish title for their king.

The metaphors Paul used to describe both the death of Jesus and its effects including sacrifice, atonement, redemption, deliverance, justification, victory, and rescue all bring resolution to the previously unresolved story of Israel. When we make the death of Jesus only about individual sinners going to heaven when they die we lose the story of Israel, the very context we need to make sense of what Paul wrote. The goal of new creation underscores God’s promises to Abraham to be the father of many nations, where Gentiles would come and worship the God of Israel (Romans 15:8-9). Let’s take a brief look at what Paul said about the death of Jesus in various letters.

Within the book of Galatians we never find the words “saved” or “salvation,” emphasizing the fact this letter is not about individuals “getting saved.” Rather the letter is about unity, that is, the fulfillment of God’s promises to Abraham of a single family made up of Jews and Gentiles worshipping the God of Israel as a unified family. Paul offered a blessing from Jesus “who gave himself for our sins to deliver us from the present evil age” (Galatians 1:4). Deliverance is Passover language, pointing the death of Jesus towards a new Passover. The “present evil age” and the “age to come” are standard ways of thinking of Jewish eschatology.

Paul summed up his unity letter to the Galatians by pointing to what really matters – new creation (Galatians 6:15). This new creation is a present reality because through the resurrection of Jesus the new age has broken into the present evil age. Jesus’ death has abolished the power of the old world. In this new creation world, Gentiles are now welcomed into the family of Abraham. The law of Moses was a temporary guardian (Galatians 3:24), but now Jesus has come and redeemed us.

Redemption, like deliverance, is Exodus language. We were slaves to sin like Israel was enslaved in Egypt and Jesus came to rescue us through his death and resurrection. Now, Jews and Gentiles have full knowledge of God through Jesus and the Spirit. The need for circumcision has passed away with the old world. Jesus has redeemed Israel from the curse of the law (Galatians 3:13), a reference back to Deuteronomy. The blessings and curses in Deuteronomy were not bestowed on individuals, but on Israel as a whole. Paul does not say Jesus bore the curse so that individual Gentiles could be forgiven. This new Exodus for Israel would require new thinking about what identified people as members of God’s family.

Galatians 3:10-14 is “penal” and “substitutionary,” but not according to the traditional narrative coming out of the Reformation. This section of Galatians is best read within the context of the covenant of vocation. Exile is over because the curse has fallen on Jesus as Israel’s substitute or representative, thus freeing Israel so she could be liberated to fulfill her vocation as a light to the Gentiles. As Israel’s representative, Jesus can act as a substitute. Jesus enters into the story of Israel and receives Israel’s curse, so the story of redemption for the world can move forward. The problem with Israel is not their sin in general, but that their sin has stalled the promise of world-wide redemption. When sins are forgiven, the powers are robbed of the power so that the goal of new creation, including the promises made to Abraham, can be reached.

Along with this new Passover/new Exodus journey toward new creation, we also have a new identity. Each person in Christ can now say, “I have been crucified with Christ. It is no longer I who live, but Christ who lives in me. And the life I now live in the flesh I live by faith in the Son of God, who loved me and gave himself for me” (Galatians 2:20). While most of Paul’s descriptions of salvation were plural, he did speak of himself in the singular as having a reshaped identity in Christ. Paul lived “within the faithfulness of the Son of God,” a better translation than “faith in the Son of God.” The revolutionary nature of the cross changes how we look at ourselves. We identify ourselves by the cross; if we were to identify ourselves by the Jewish law there would be no reason for Jesus to die (Galatians 2:21).

Wright sums up three points in locating the connection in Galatians between the death of Jesus and the inclusion of Gentiles into the family of God. First, God has condemned the present evil age and broken in with the “age to come,” freeing all people from evil and sin. Second, God has done this through the death of Jesus who died for our sins. In Christ no one is labeled “sinner” or “unclean” or “excluded from the family of God.” Third, Jews in Christ have a radical new identity formed around the death and resurrection of Jesus.

Galatians is about unity in Christ, although older interpretations of Galatians going back to the Reformation tend to read it as a text advising the church not to attempt to earn “righteousness” or salvation by good works. Any attempt to read a rebuke of “legalism” in Galatians is to miss Paul’s point. The old age is passing away, which implies the works of the flesh (Galatians 5:19-21) associated with that age. The Spirit-driven age to come ushers in a new lifestyle typified by the fruit of the Spirit (Galatians 5:22-23). Moral energy and effort for those in Christ is not connected to earning one’s salvation, but in recognizing what has happened in Christ. This new Passover event was a means towards the kingdom’s triumph over the powers of the present evil age. A new kind of unity and holiness for the people of God is the appropriate response to this revolution. To live according to the ethics of the present evil age is to deny that the age to come has arrived through the death and resurrection of Jesus.

As with the book of Galatians, Paul does not give us a clear explanation of how or why the death of Jesus accomplished what it does. Paul does continue with the use of Passover imagery. “For Christ, our Passover lamb, has been sacrificed” (1 Corinthians 5:6). He connected the practice of communion with the “new covenant in my blood” and the “proclamation of the Lord’s death” (1 Corinthians 11:25-26). We have seen Paul’s important statement regarding the death of Christ “for our sins in accordance with the Scriptures” (1 Corinthians 15:3). This sacrificial death, and the resurrection that follows, defeated sin and death for us that we may share in his victory (1 Corinthians 15:57). Jesus’ inauguration of the kingdom of God through death overturned all conventional approaches to power.

The followers of Jesus exercise power on the earth through suffering: “For we who live are always being given over to death for Jesus’ sake, so that the life of Jesus also may be manifested in our mortal flesh” (2 Corinthians 4:11). The cross is not simply a mechanism by which salvation occurs. The cross shapes our lives as followers of Jesus and the cross reveals to us what God is like. According to Wright, “The Messiah’s crucifixion unveiled the very nature of God himself at work in generous self-giving love to overthrow all power structures by dealing with the sin that had given them their power, that same divine nature would now be at work through the ministry of the gospel not only through what was said, but through the character and the circumstances of the people who were saying it” (251). This understanding of the cross fits within the covenant of vocation. The cross was the means by which our sins are dealt with and the cross becomes the way we live as the image-bearing creatures of the Creator God.

According to Paul, as we are in Christ, we have entered into God’s new creation and have received a job to do, that is the ministry of reconciliation (2 Corinthians 5:17-18). God in Christ was reconciling the world to himself, not so we could keep the rules according to the works contract, but so we could be agents of reconciliation in God’s world: “For our sake he made him to be sin who knew no sin, so that in him we might (embody) the righteousness of God” (2 Corinthians 5:21).

Those working from the perspective of the works contract see in this verse what has been called “double imputation,” where our sin was imputed to Christ and his “righteousness” was imputed to us. However, in the context of the ministry of reconciliation (and the larger context of the covenant of vocation), Paul was not talking about a righteousness we receive, but a righteousness we embody. The “righteousness of God” in this verse is not a moralistic status, but a covenant status. God’s own righteousness, or “rightness,” speaks of God’s fidelity to the covenant. God made him, Jesus, who knew no sin to bear our sins, taking them away through his death, so we could embody God’s faithfulness to the covenant. Jesus, in reflection of God’s love, dies innocently on behalf of the guilty that we might be restored in order to reflect God’s fidelity and love into all creation.

In Philippians, Paul recorded what was either an ancient hymn or poem (see Philippians 2:6-11). At the very heart of this poem is the line “even death on the cross.” This poem tells the story of Jesus with the cross at the center. In the great crescendo we see the victory of Jesus over all powers and creatures in heaven, on earth, and under the earth. This exaltation of Jesus is kingdom-language marking the inauguration of the kingdom of God led by King Jesus. The poem also noted that Jesus took the “form of a servant,” echoing Isaiah 40-55 and the servant of the Lord. The kingdom of God is established precisely by destroying the power of idolatry and taking away the power of sin and death.

According to Colossians 2:13-15, Jesus at the cross disarmed “the rulers and authorities.” These ruling powers are both the earthly rulers of Rome and their appointees (namely King Herod in the Judean province of the Roman empire), as well as the invisible rulers, the dark forces that manipulate earthly power structures. Jesus in his death triumphs over them, putting them to shame, because their system of power and domination results in putting to death not just an innocent man, but God in human flesh.

Earthly rulers are able to rule through the power of punishment (i.e. death) and through the enslaving power of idolatry. In ancient Rome, the Caesar was worshipped as divine and the pantheon of gods offered idolatry to the masses. When human beings worship in the place of God that which is not God, corruption of their humanity begins. But through the death of Jesus sins are forgiven and taken away, breaking the power of sin and idolatry and reconciling broken humanity to their Creator. In this act, the invisible powers at work within idolatry lose their power.