I am blogging my way through N.T. Wright’s book The Day the Revolution Began, creating an outline of the book as a small group study I am leading at our church. This is the first of six blogs in this series. All quotations followed by a number in parenthesis are quotes from the book.

Getting Things Started

The Day the Revolution Began (Chapters 1-3)

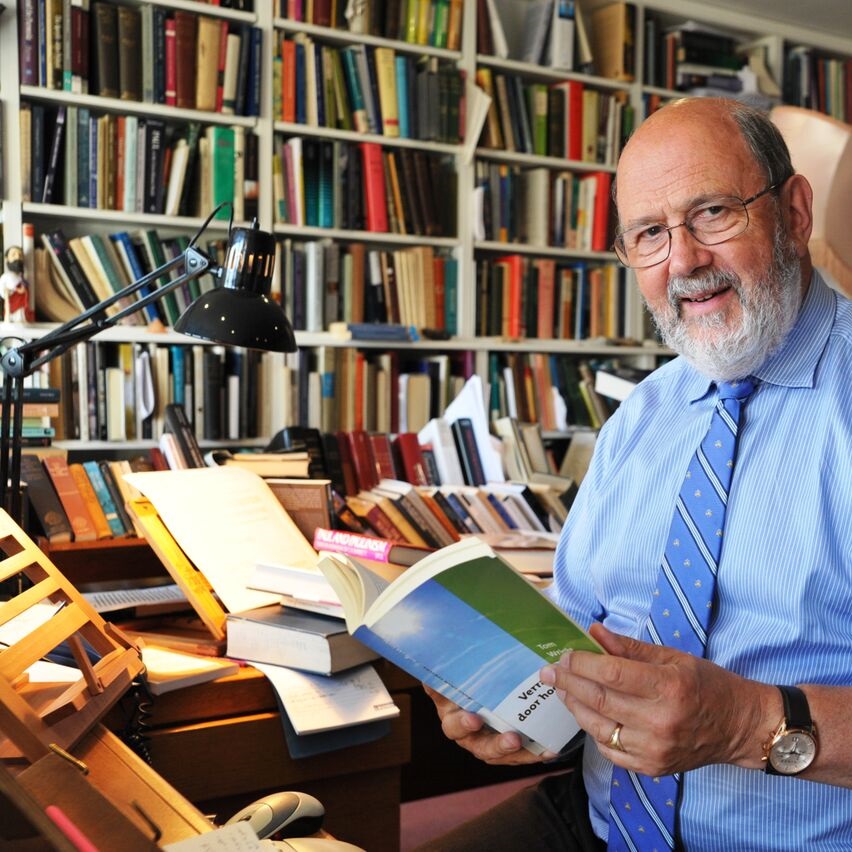

N.T. Wright is not only a brilliant theologian, he is a warm and colorful writer, which is a rare combination for a Bible scholar. The Day the Revolution Began contains his thoughts on the meaning of the death of Jesus on the cross. It is a book of theology and “theology” is not a bad word. Christian theology is a 2,000 year-old conversation among preachers and prophets, scholars and shoemakers. Theology is not the study of God as much at it is a study of how God has chosen to reveal himself. God has revealed himself in creation, in Scripture, in the sacraments, in prayer, in the long winding story of the Great Tradition and the broad history of the church.

Theology is not reserved for intellectuals, although we welcome and value their contribution; theology is a whole-people-of-God activity.

Let’s define some key terms and phrases…

Post-Christian: the cultural shift in Europe and the United States where the virtues and values of the Christian faith no longer have a dominant place in public life.

Atonement theories: While we confess in the Nicene Creed “for us and for our salvation he came down from heaven…for our sake he was crucified under Pontius Pilate,” the church has never definitively defined how the death of Jesus saves us. Throughout history, Christians have constructed theories to explain how the death of Jesus atones for our sin.

- Recapitulation Theory: Jesus comes to sum-up the entire life of Adam including taking Adam’s sin and experience death to become the head of a new humanity.

- Ransom Theory: Jesus’ death is a payment made for the debt incurred by sin.

- Moral Influence Theory: Jesus dies as a sacrifice for sin as an example for us to follow.

- Christus Victor: Jesus’ death sets us free from the power of sin and Satan.

- Satisfaction Theory: Jesus’ death satisfies God’s demands for justice and honor.

- Propitiation Theory: Jesus’ death turns the wrath/anger of God.

- Penal Substitution Theory: Jesus dies in the place of sinners taking upon himself the penalty sinners deserve.

In this book, Wright tends to critique satisfaction, propitiation, and penal substitution.

The Reformers: The Protestant reformers of the 16th century include figures like Martin Luther, John Calvin, Menno Simmons, Huldrych Zwingli, Thomas Cranmer, and others.

Eschatology: A theological understanding of “end things,” including heaven, hell, and the second coming of Christ

Roman-Greco World: The “Greco” part of that description refers to the influence of Greek culture upon the Roman Empire. The Romans had built their mighty empire on top of the fallen and divided Greek empire.

Chapter 1: A Vitally Important Scandal

In the opening paragraph Wright imagines the death of Jesus in its historical setting without much fanfare. Rome has executed another political rival because this is what Rome does. But death is not the end of the Jesus story. As followers of Jesus look back at the cross through the resurrection they see that in Jesus “his death had launched a revolution” (3).

The resurrection completely changes how we see the cross. Instead of reflecting on the cross as a sad, pitiful end to another Jewish revolutionary, we see the cross as the beginning of a worldwide revolution. We often assume Jesus died so we could go to heaven when we die, when the early Christians talked about the death of Jesus in ways that were “bigger,” “more dangerous,” and “more explosive.”

A bigger view of the cross reveals the death of Jesus makes a huge difference not just for individuals but for the entire world, which prompts the why questions. Why is the cross so powerful? What does the cross continue to captivate and convict? Why does the death of Christ continue to change the lives of millions?

According to Wright, “You don’t have to have a theory about why the cross is so powerful before you can be moved and changed, before you can know yourself loved and forgiven, because of Jesus’ death” (12). We don’t have to fully understand the cross any more than we have be able to explain how the elements of communion connect us with Jesus; we just need to be present in humility and faith. And yet, if we want to grow in the faith it is worth our time to explore with why questions.

Asking ourselves “why did Jesus die” has two different sets of questions including historical questions: Why did Jewish leaders and the Roman governor want to execute Jesus? And theological questions: What does the death of Jesus reveal about God? What did the death of Jesus accomplish?

Chapter 2: Wrestling with the Cross, Then and Now

How did this awful implement of torture and death become the enduring symbol of a world-wide movement? Roman crucifixion was so shameful that it wasn’t talked about openly in the first century world. Early followers of Jesus could have brushed over the cross and focused solely on the resurrection of Jesus in order to avoid the ridicule and confusion, but they did just the opposite. Early Christians celebrated the cross, but they did not define it. The important early creeds of the church did not contain what we now know as atonement theories.

Understanding the cross for us modern Christians is possible because we have 2,000 years of reflection on the meaning of the cross, but we start not with the theological puzzles created by theologians over the years. Rather we start with looking at the crucifixion of Jesus within the context of the big story the Bible is telling.

Three recurring themes regarding the cross can be found in writings of the early church fathers:

1. Through the cross God secured victory over the powers of evil.

2. Jesus died in our place so we do not need to experience death.

3. Jesus’ death was sacrificial.

These themes did not exist as stand-alone theories, but as metaphors in the story the Bible tells. For the Orthodox it was not necessary to specify a specific explanation to explain why the death of Jesus was necessary or how exactly the cross saves. The current debates surrounding the meaning of the crucifixion are rooted in the Protestant Reformation of the 16th century.

The Reformers did not devote as much attention to the future of God’s people as they did to the salvation of God’s people, which is problematic because understanding the implications of salvation and the direction salvation takes us is necessary to understand how the death of Jesus saves. The Reformation was, in part, a response to two doctrines within Catholicism: Purgatory and the Mass. Arguing against these two doctrines had a direct effect on how the Reformers talked about the cross.

Purgatory, during Medieval Catholicism, was the belief in a place of temporary punishment, whereby Christians could suffer some for their sins before going to heaven. The Reformers opposed this teaching. Behind this doctrine was the emphasis within Roman Catholicism on heaven or hell as the final destination of the human soul. Absent from their view of the future was new creation. Heaven was the goal, not the reconciliation of heaven and earth.

The Reformers argued that Christians did not need to suffer after they died in order to be purified of the sins and enter heaven because, according to their interpretation of the cross, Jesus was punished for sinners on the cross. In this regard, Jesus not only bore our sins but also the wrath of God against sins.

The particular point of opposition for the Reformers in their critique of the celebration of the Mass was the Roman Catholic understanding that in one sense the priest was sacrificing Jesus to share his body and blood with the congregation. The Reformers again looked to the cross to point out the impossibility of sacrificing and re-sacrificing Jesus at every Mass. Jesus suffered on the cross in our place once for all.

As with purgatory, the Reformers drew upon penal substitutionary atonement to form their argument against the Mass and their interpretation of a justification by works. What they missed was questioning the assumption of divine wrath and the need somehow for that wrath to pacified.

The Reformers provided correct answers. We are indeed justified by faith and not by works, but the problem was not that we required justification because God was angry and his justice required his anger to be “satisfied.” The right answers about justification to the wrong questions about pacifying an angry god mixed with a limited vision of the future has created what Wright calls a “paganized vision” of the cross, a vision not consistent with the early Christians.

For Wright, atonement is connected to eschatology. If the end is not enjoying God forever in a disembodied heaven and is instead bodily resurrection and new creation, then maybe the death of Christ is not a matter of appeasing an angry God so we can go to heaven upon death.

For Wright, “The cross was the moment when something happened as a result of which the world became a different place, inaugurating God’s future plan. The revolution began then and there; Jesus resurrection was the first sign that it was indeed underway.” (34)

By the 1800s, the popular assumption in Protestant Europe and the United States had become Jesus died for my sins to take me to heaven when I die and because my sin incurred the wrath of God my Savior died for me. The problem with this heightened view on the individual was the division it created between personal sins and evil in the world.

The most popular history-ignoring equation for modern American evangelicals is one that goes like this: You have sinned. Sin separates you from God. Jesus died for your sins to bridge the gap. Accept Jesus as your personal Lord and Savior and you can have a relationship with God. This formula is not altogether untrue, but neither is it what we find in the New Testament, at least not the New Testament read in the context of history of the first-century Jewish and Roman worlds.

Popular atonement theologies saw the cross as the remedy for our personal sins while the so-called problem of evil had to be dealt with by means other than a deep reflection on the cross. In other words, the cross saves us from sin so we can go to heaven, but systemic sin and evil on a global scale needs to be dealt with in some other way, as if the Gospel has nothing to say to global evil.

Some people hear the “gospel” as God is angry, but Jesus satisfied the wrath (anger) of God for us. This version of the Gospel leaves many with the impression that God is not love, but an angry petulant god who desires blood. Some people reject the faith over this misunderstanding of cross. Others reread the Scriptures and the early church fathers to discover the cross reveals the co-suffering, self-giving love of God that has defeated the powers of sin, death, and hell. Indeed this is the bigger story that the Bible is telling.

Questioning the necessity of violence and punishment in considering the meaning of the cross has raised a number of questions: Does the God and Father of Jesus use violence for his purposes? Does the Father use violence against the Son? What about divine punishment? Does God use violence to punish people? Some people hear the Gospel sounding something like: “God so hated the world, that he killed his only son” (43). This rewriting of John 3:16 is the very distortion we end up with if our view of God is one of an angry deity hell-bent on violent punishment.

Some people will argue that if God is willing to employ violence to accomplish his saving, forgiving work, then we human beings, created in his image have an example to follow. We too can justify violence if we have enough righteous anger. How Christians talked about issues like global terrorism or capital punishment are rooted in our views of the atonement. If we are to reject the view that depicts a grouchy god using violence to pacify that god’s own anger in the death of Jesus, then what are the alternatives?

First, the death of Jesus wins a decisive victory over the “powers” of this dark and evil age dominated by sin and death. This view raises a number of questions that Wright will explore later on in the book. Second, the death of Christ reveals the love of God in a unique and powerful way that becomes an examples for us to follow.

However this view also raises questions, primarily: How does Jesus’ death necessarily reveal the love of God? I could try to prove to my wife that I love her by jumping into a freezing cold lake during the middle of winter, but that doesn’t demonstrate love or courage. It would really only demonstrate my own stupidity. Unless the death of Jesus achieved something that could be achieved no other way, then the death of Jesus is neither a demonstration of God’s love nor an example to follow.

Chapter 3: The Cross in Its First-Century Setting

We understand the various meanings of the cross when we seek to understand it in the historical context of the death of Jesus and the writers of the New Testament. A wide-angle view of the history surrounding the crucifixion begins with a look at the world of the Roman Empire built on top of an older Greek culture.

Crucifixion was perfected by the Roman Empire as a way to execute rebels, traitors, slaves, and violent criminals in public to remind people of the might and sovereignty of the empire. Romans and Jews alike viewed crucifixion as abhorrent and a public humiliation; it was too ghastly to talk about openly.

Crucifixion had both political and cultural meanings, which helps us to understand the cross theologically. Roman crosses symbolized the all-encompassing power of Rome. Jesus, according to Wright, “grew up under the shadow of the cross” (57). Jewish revolts had sprung up in the days before Jesus and Rome crushed them every time. Jesus grew up hearing the stories and seeing the horror of the Roman cross.

This historical account of crucifixion stands in the background of how early Christians understood the meaning of the cross in general and Jesus’ death in particular. Their view of the cross was loaded with social, political, and religious meanings.

* Socially, the cross signified the superiority of Rome.

* Politically, the cross implied Rome was running things.

* Religiously, the Roman emperor was revered as the divine and thus more powerful than the local “gods” worshipped by the Jews or other people.

The question for readers of the New Testament is: How did the cross acquire such a fundamentally different meaning by the followers of Jesus? Wright leads us into a discovery of the meaning of crucifixion from the perspective of the earliest Christians which will underscore the biblical and revolutionary roots of the cross in early Christian thought.

The ancient world of Greece and Rome were filled with stories of people who were sacrificed, or sacrificed themselves, to secure blessings or turn away divine wrath. These stories are more rare in ancient Israel. Wright will touch on those later. As Jewish leaders were plotting Jesus’ death, Caiaphas argues that it is better that one man die for the people, so the nation may be spared. According to Wright this view is found more often in pagan literature than in the Hebrew Scriptures.

In pagan literature those who were dying on behalf of other people were dying what would have been considered an honorable sacrificial death. No one living in the Roman Empire would have called death by crucifixion “honorable.” For Christians to speak of the death of Jesus upon the cross with any kind of significance would be rejected by Roman citizens as foolishness.

Within the wider cultural context of the Greco-Roman world, the more narrow historical context to examine when considering the meaning of the cross is the Jewish world of the first century. Wright mentions three important ideas regarding the Jewish context for the death of Jesus.

First, no Jewish festival was more important than the Passover, the commemoration of the time when the God of Israel delivered the people of Israel from Egyptian slavery under the heavy hand of Pharaoh. When Jesus chose to reveal, in clearest terms, the meaning of his death he did so at Passover meal, his final meal with his disciples before his arrest. The Passover event became a primary way for the early Christians to work towards understanding the implications of the death of Jesus.

Second, Jewish people of Jesus’ day saw themselves as exiles, living in their homeland, but still under the yoke of a foreign, pagan, occupying force. The Babylonian exile five-plus centuries before Jesus had been extended into the present-day. According to the prophet Jeremiah, God promised to do a new thing, to make a new covenant, one in which sins would be forgiven, bringing their exile to an end.

Third, while many first-century Jews expected God’s Messiah, God’s reigning King to come to enact this new covenant, none of them expected Messiah to come in the way Jesus did. They looked for Messiah to come to restore the kingdom to Israel, but none expected Messiah to suffer in the way Jesus did.

Wright will dedicate a large portion of the book to how early Christians read the Old Testament in light of the death, burial, and resurrection of Jesus, but he offers a few observations regarding the specific world of the first-century Christians. This world existed within a Jewish world, within the world of the Roman empire.

The themes of the New Testament writers use metaphors from the Jewish world, but in new and surprising ways. Wright will show how the themes work together later in the book. The Gospels (Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John) fit together with the Epistles (the letters of Paul, Peter, John, and others) in a cohesive way under the banner of the early Christian statement: “The Messiah died for our sins in accordance with the Bible,” (1 Corinthians 15:3).

How do we see the meaning of the cross work out in the diversity of writing and writers in the New Testament? Wright sketches out his plan to answer those questions at the end of this chapter with these points:

- We need to reject the popular view of going to heaven when we die, with the more biblical view of the new heavens and new earth at the end of the age.

- Sin isn’t what prevents us from going to heaven, but sin, and the idolatry standing behind it, keeps us from bearing the image of God in and for the world.

- Idols have been empowered by human idolatry. God’s new creation to break in and renew the old broken-down creation, the power of idolatry must be broken.

- God’s act of dethroning the power of idols is God’s way of dealing with sin so that human beings can be restored to God’s image-bearers and thus fulfill their primary vocation.

- God’s single plan of dealing with human plight, sin, corruption, and idolatry is centered in the story of Israel.

- Jesus comes as Israel’s Messiah and Israel’s representative to do for Israel, and ultimately for the world, what Israel could not do for herself.

- The climactic act of Jesus’ death enacts God’s revolutionary plan to rescue the world God loves.

Discussion Questions

1. How would you describe your earliest encounter with the message of the cross? Was in one of awe, fear, love, or devotion? Share your story.

2. What value is there in becoming aware of the history of the church?

3. In what ways is our understanding of the end (eschatology) connected to our understanding of the meaning of the cross (atonement)?

4. Do you now or have you ever had a vision of an angry god who determined to punish you for your wrong doing? Where do you think that image came from?

5. How do things change for you if you begin to see salvation in terms of what God is doing in and for the world more than simply what God is doing for you?

6. Where are the differences in how people hear: “God so hated the world that he killed his only son” and “God so loved the world that he gave his only son”?

7. Why do you think Jesus waited until the Passover (last supper) with his disciples to speak so clearly about his pending death?

8. Why do you think so many Jewish people did not expect the Messiah to come the way Jesus did?

e heart of the debate between Calvinism and Arminianism over the doctrine of election is the understanding of God’s act of predestination.

e heart of the debate between Calvinism and Arminianism over the doctrine of election is the understanding of God’s act of predestination.